CW: This post talks about gender-based violence.

As a Hindu-majority nation, caste deeply affects the way that society functions in Nepal, though with so many vastly different ethnic groups it is a complicated story. I didn’t know much about the Nepali caste system before I came here, and as a foreigner I can’t really know what it’s like to live within it. Caste cannot be separated from other identity markers, such as religion, language, skin color, and more, especially in Nepal, and so having only been here for less than ten months, mostly in Kathmandu, it’s impossible for me to have a full picture. I don’t profess to be an expert of any sort on the subject, but I can give basic information on how the caste system works in Nepal and I felt I should speak to the experiences that I have had and ways in which I’ve noticed caste play a role in the world around me.

It is important to understand that Nepal is populated by more than a hundred different ethnic groups, many of which are indigenous to the land, and all of which have their own distinct cultures. These different groups have all been interacting for hundreds of years, and many of them have influenced each other culturally during that time. The main form of differentiation between ethnic groups tends to be language, though, and like any ethnicity, each person holds their own identity, with factors like religion, appearance, name, and physical location all playing a role. There is no real majority ethnic group in Nepal: in fact, no one group makes up more than 20% of the population, with the vast majority making up under 5%, or even under 2%.

Many of Nepal’s ethnic groups have their own traditional social hierarchies, but caste specifically is a Hindu construction, and the prevailing one in the country since the unification of Nepal in the 18th century under Hindu rule (the unification itself is a somewhat violent and complicated story). Because of the varied identities of the different groups in Nepal, caste was met with different levels of acceptance as Hinduism was introduced and spread throughout the area over the course of hundreds of years. Many traditionally Hindu ethnic groups, such as Newar or Madhesh peoples, have their own internal caste systems, leading to complex sub-caste categories (especially among the Newars, since they are commonly both Buddhist and Hindu, and some are not Hindu at all).

Other non-Hindu groups, regardless of their acceptance of the caste system, have been incorporated into it and assigned a caste, though often it is simply their ethnic group. Many of the majority-Buddhist groups or followers of indigenous religions have simply been grouped together under a relatively low-caste umbrella. All Nepalis understand caste and the distinction between ethnic groups in their society, but the lens through which they see those distinctions and the amount to which they care about high- or low-caste status depends on their own culture and upbringing. The extent to which caste affects their life depends on where they live and, of course, their caste—one of the privileges of being high-caste is not always seeing how caste affects one’s life.

The most important group to talk about within the conversation of caste is Khas Arya, a Hindu group in Nepal which makes up the largest individual percentage of the population and ascribes most closely to the caste groupings. The leaders who were responsible for the unification of Nepal were members of Khas Arya, and thus founded their kingdom on principles of caste separation, including their four traditional castes (from high- to low-caste): Brahmin, Kshatriya (often “Chhetri” in Nepal), Vaishya, and Sudra. There is also a fifth group, known as Dalit, who are considered below all of these groups and untouchable. When speaking about caste in Nepal, unless an ethnic group is specified (i.e. Newar Chhetri or Madhesh Brahmin), it is assumed that the person or group being referred to is Khas Arya.

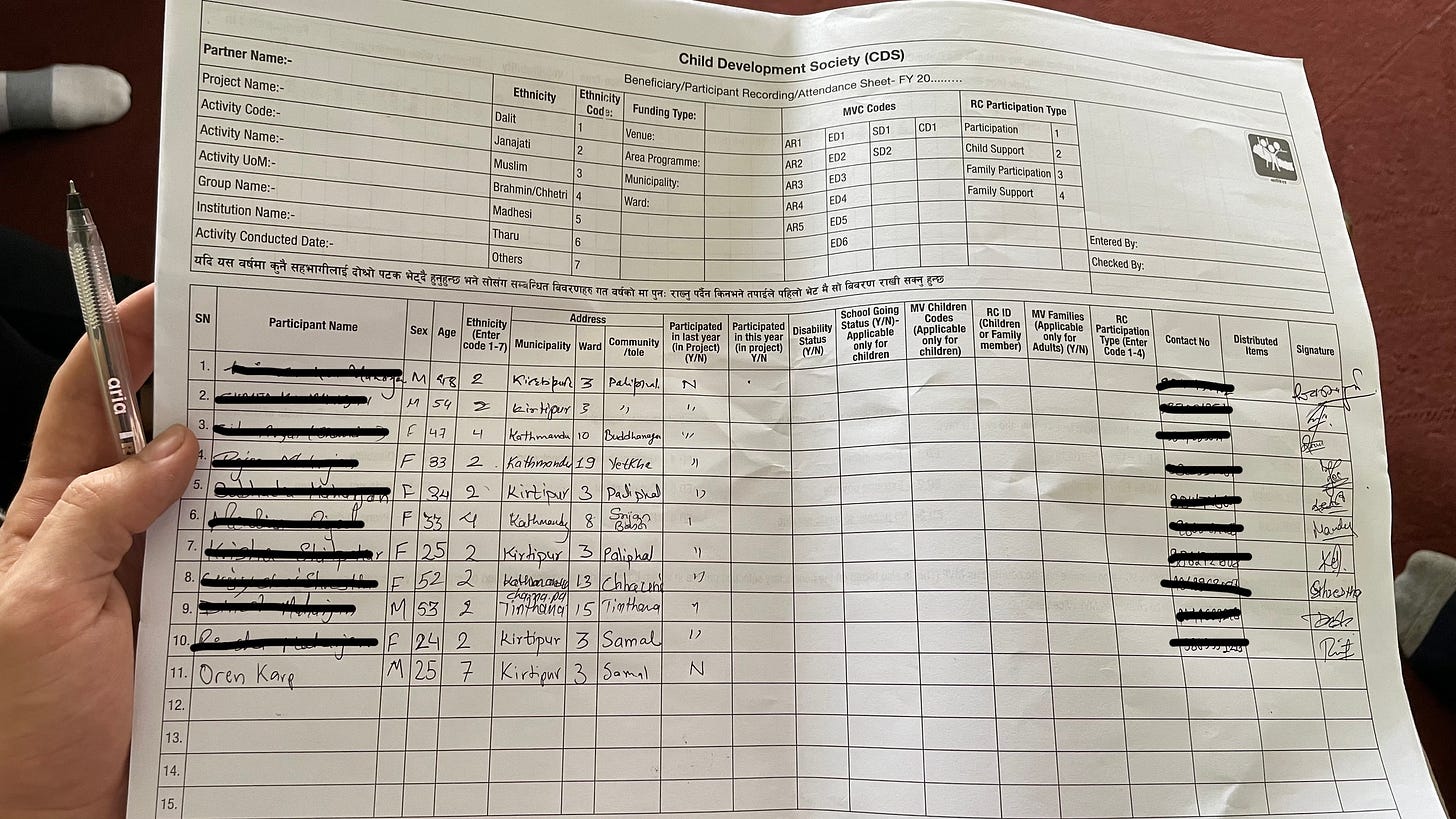

Many Nepalis are able to distinguish caste in daily life with a relative ease that boggles my mind as a foreigner. Caste certainly overlaps with physical appearance, and different ethnic groups can have widely different facial features which are spoken about bluntly. Lighter skin is seen as a widely favorable trait, and many cosmetic products here include “skin lightening” ingredients—buying even sunscreen or moisturizer without any kind of lightening agent can be difficult here. But skin color and face shape are not reliable markers of caste, and neither is language necessarily. Instead, the way in which most Nepalis tell a person’s caste is from their last name. Culturally, one is expected to state their full name here when giving an introduction, and from the surname Nepalis can place a person into their mental catalog of ethnic groups and castes. I have been here for long enough to recognize many of the ethnic groups, such as Tamang or Limbu (there are many of both at my school), but when I hear a name that is not specifically an ethnic group, it means nothing to me. I am constantly amazed that so many Nepalis are able to remember all of the different groups and names and social associations with each one.

Caste is extremely stratified, with status assigned at birth and no opportunities for mobility, since one’s denomination is religiously seen as a product of the cycle of birth and rebirth and thus not only divinely chosen but also justified due to behavior in a past life. Traditionally, one’s caste was a marker of not only one’s social class but also one’s occupation, with high-caste roles including priests or knights, and low-caste roles including traders and laborers. Like any other form of social stratification, power is collected at the top through the oppression of those on the bottom, and there is no internal impetus for those in power to change the system which advantages them.

One main way in which the caste system has been upheld is through traditionally strict endogamy—a social structure in which marriage happens only within a specific group of people, in this case a caste or ethnic group. This is highly tied to the ideas of “purity” that go along with caste, and the idea that someone of high caste cannot marry someone of a lower caste, since that would make them “impure” (especially women). By only allowing for marriage within one’s own group, the ability for mobility even between generations is cut off. Things have begun to change in modern times, and inter-group dating and marriage is beginning to become more common—especially in the city—but there is still a massive amount of social pressure (and often direct parental pressure) to marry within one’s own caste or ethnic group. There are practical factors, like shared language and preservation of culture, though it is deeply tied to social hierarchy as well. Those who marry outside of their own group often have to leave their home; those of high caste are seen as having lowered their position, and those of low caste risk physical violence from angry high-caste family or community members.

Because the succeeding rulers of Nepal after unification continued to come from high-caste Khas Arya until the abolishment of the monarchy in 2008, caste was historically a very explicit part of the government system. In 1854, a civil code was instituted by the king of Nepal called Muluki Ain, which was rooted in Hindu law and very specifically broke down caste hierarchy and assignments within the country, effectively making caste into law. Because it was put in place by members of Khas Arya, it even put other Hindu groups of equivalent caste below those of Khas Arya, and paved the way for various discriminatory laws against members of low castes. It was also an attempt to formally incorporate the non-Hindu groups of the country into a Hindu system and assign them to different castes. The Muluki Ain was seen as an oppressive political tool of the then regime, which lasted more than one hundred years, and once the dynasty ended in 1951 the rules were openly flaunted though still technically in place. The Muluki Ain were officially replaced in 1963, and it became illegal to discriminate in Nepal on the basis of caste.

However, caste is still a large part of everyday life for many in Nepal, especially those of low caste, such as Dalits. Though discrimination is illegal and all castes are meant to be treated equally by the law, it is not so simple in reality. For example, education is legally meant to be free and available to all castes, but the literacy rate for Dalits remains very low compared to Brahmins or Chhetris, and many members of civil service and government in Nepal today still come from the same high-caste groups. Much of this is tied up in economics, since those of low caste are far more likely to live in poverty than those of high caste, and thus many Dalit children are forced to find a way to make money working or begging rather than going to school. Of course, there are no absolutes, but when Nepali society is looked at as a whole, it is very clear that there are still strong associations between caste and socio-economic status.

As Nepali society grows and changes, and especially with the rapid urbanization of the country, it seems that the importance of caste is decreasing for many for simple, pragmatic reasons. This is probably due, once again, to economics—many Nepalis see money, or lack thereof, as the main obstacle to their success. And with that comes the converse conclusion, that once one obtains money, some level of social mobility is possible. It’s not much, but compared to a system in which no mobility at all is possible, even the opportunity to work and make money for oneself in order to improve one’s place in society appears fairly radical. Of course, capitalism comes with its own forms of stratification—and because caste is correlated strongly with economic status, it begs the question: is an economically stratified society really any different from one stratified based on caste?

Additionally, physical location and access to resources is seen as a huge socio-economic factor. Whether a person is located in a city and has access to the money, education, health care, etc. that is much more easily obtained in a city seems to be more important to many Nepalis than caste in terms of creating social change. However, in many village areas, social structures tend to be more conservative and caste can still play a very large role in the lives of Nepalis. Caste-related violence is sadly still not an uncommon occurrence in Nepal, often without repercussions for the high-caste perpetrators. This is tied up in the patriarchal nature of caste as well, since much caste-based violence is either aimed at women of low caste or at men of low caste who are involved with women of high-caste. “Impure” low-caste men marrying high-caste women is seen by other high-caste men as an attack on high-caste women’s purity, though the same standard does not apply when it comes to gender-based violence committed by those same high-caste men against low-caste women. Either way, the results are the same: there are often no consequences for the high-caste men, and the social inequality which they are upholding is perpetuated through violence and fear.

There are ongoing social justice campaigns and activists in Nepal who are fighting for the rights of low-caste and minority ethnic groups. They have met with some success on a national level: following the second peoples’ movement in 2006, the new constitution specifically outlines rights of women, low-caste and minority ethnic groups. More than half of the parliament is elected through proportional representation (PR), meaning that they are elected with the general population’s votes treated as a single constituency, and all political parties are required to nominate 50% women candidates for those PR seats. Additionally, seats are set aside on all levels of government for low-caste and ethnic minority groups proportional to their populations, with half of those seats reserved for women. However, many of these seats commonly go unfilled, with no candidates at all, and the effectiveness of the government in combatting caste-based discrimination is debated. There appears to be much work still to be done in changing social attitudes.

Many of the travelers I have met in Nepal have no knowledge of the caste system here, or that there even is a caste system here. For those foreigners who are outside of the caste system, it can be completely invisible, but for so many Nepalis, it is a daily fact of life. It is often hard to tell if the way I see someone being treated is related to caste, since factors like economic status play a big difference, though of course the two intersect. All I can really say is that there are so many more dynamics underlying the interactions that I see, dynamics that it would take me years to begin to understand. In the meantime, I encourage anybody thinking of visiting Nepal to please come, and to take the time to learn more about caste from people like Sarita Pariyar (and many, many Indian activists as well), who have made this their life’s work. There are so many amazing ways to educate yourself!

Until next time: peace!

Much love,

Oren